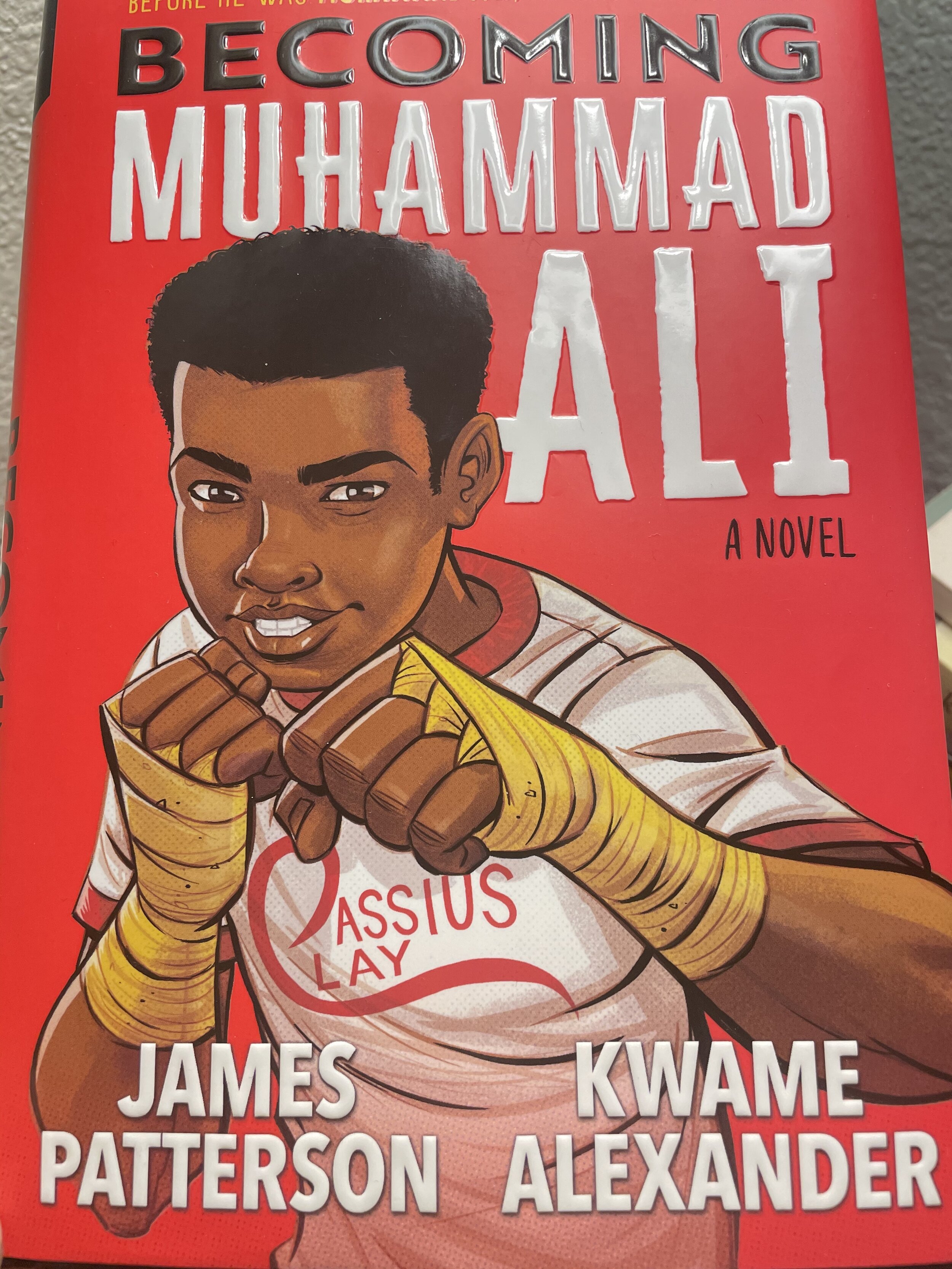

Becoming Muhammad Ali

By Kwame Alexander and James Patterson

Listen to Ali.

The video below on the left is an interview with Dick Cavett in 1970 where Ali speaks out against the Vietnam War. The dynamic between the two men is really something. The video on the right is a track from Ali’s recorded album of spoken poetry. And, believe it or not, in 1967, he collaborated with Marianne Moore, a Pulitzer Prize winning poet, and the so-called “elderly queen mother of American letters,” on this poem.

I loved this collaboration of Patterson and Kwame Alexander. As soon as I heard about this book, I knew I wanted Good Trouble For Kids to feature it. First, because I am so taken by Ali’s bravery in refusing to go to Vietnam when he was at his peak at an athlete. He can certainly be seen as a model of the athlete practicing social justice – leading perhaps to the most recent example of Colin Kaepernick. Second, because of Ali’s phenomenal use of language – his outspoken poetry of the self; I don’t know what else to call it. (“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”) There are other athletes who have been described poetically (e.g, sports journalists comparing Lynn Swann to ballet dancers Nijinsky or Nureyev; or Michael Jordan’s seeming ability to literally glide through the air - defying gravity - being described as poetry in motion). But Ali’s use of language was something else. In Round 10, the authors, using Lucky’s voice, acknowledge the unusualness of this. I particularly like that that poetry of language was not determined or defined by academic institutions. It was who he was, just as his continued commitment to social justice and philanthropic causes – beyond his extraordinary display of civil disobedience – spoke to his character.

I used to love boxing. I was enamored of it perhaps in the same way Joyce Carol Oates was enamored of it, and as she wrote about it in On Boxing, which I read when it came out both because I was taken with some of Oates’ prolific output, and because I was incredibly curious as to why boxing appealed to her. All these years later, I still can’t quite figure out why it appealed to me, and in fact am somewhat disturbed by how I was entertained by what on some level is truly just an exhibition of violence. Was it the one on one in the ring that attracted me (but then I must face echoes of the Greek arena), or the sheer physicality of it? the beauty of the male physique? (which then entails an examination of how the Black male body specifically has been exoticized). The questions themselves are uncomfortable. The sport finally fell apart for me when Mike Tyson bit Evander Holyfield’s ear – as if that moment somehow defined the brutality of a sport that had of course always been bloody, brutal, and brain-damaging. And of course there had always been the racial undertones of the Great White Hope; the white gaze on the Black Body; the complexity of Joe Louis fighting against a German in the Olympics and the symbolism of that in a country (the US) plagued with racism and Jim Crow, and a country (Germany) about to publicly embark on outright genocide of a people they deemed a lower race – with 6 million Jews murdered at war’s end. But growing up in Poughkeepsie, NY, not far from the Catskills where Tyson trained with Cus D’Amato, much as Ali trained with his white trainer, Joe Martin, I sucked up the story of a boy like Mike Tyson who had nothing and “made it.” I am embarrassed by that now, and it begs the question of what did I think “making it” meant? When it comes to Ali, and especially in light of Good Trouble For Kids, Ali “made it” in the right ways – as a model for civil disobedience; of how to practice philanthropy; of how to take pride in one’s Blackness; of how to elevate sportsmanship into a way of living and being in the world.

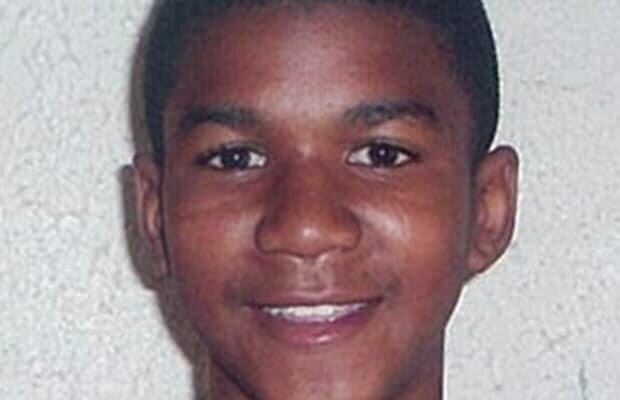

Patterson’s and Alexander’s story of the young Cassius Clay “becoming Ali” capture the feel of this time in Ali’s life, particularly the divide between Black and white worlds (you can see here the Jim Crow laws that were in place in Kentucky and other Southern States). The more I study the civil rights era, the more I am moved and heartbroken by the bravery of Emmett Till’s mother insisting that America confront the destruction of her son’s body by her refusal to have a closed casket. What Mamie Till did was force America to bear witness to what white supremacy had done to her son. It necessitated a public accounting, and made the murder of Emmett Till a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement, as I wrote about in my write-up on Marilyn Nelson’s book A Wreath For Emmett Till (featured in our 15+ category in January 2021).Think of the impact of Till’s murder on boys around his age, much like Ali was. Today, one cannot help but think of Trayvon Martin’s face, or of Tamir Rice’s – two of too many gunned down by police in their youth. The trajectory of Ali’s life in this light – the dangers ever present to his body out of the ring – must not be forgotten. Patterson and Alexander convey this powerfully in their book.

“Narrative: Ali”

A Poem in Twelve Rounds

The poet Elizabeth Alexander, in her twelve verse poem entitled “Narrative: Ali,” also written in Ali’s imagined voice, has an entire verse conjuring Ali’s reaction to Emmett Till’s murder.

In conclusion, I want to point out the authors’ use of a “Where I’m From” poem on pages 28-29, because it is a technique so often used in bibliotherapy and a wonderful tool for educators (including parents who are home-schooling). I will definitely bring this version into workshops. Appalachian poet George Ella Lyon is often cited as the creator of this form. The first line of her poem reads:

I am from clothespins,/ from Clorox and carbon-tetrachloride./ I am from the dirt under the back porch.

I used this as a first exercise with a writing group at Denver Women’s Correctional Facility, and also with a women’s writing group. It was successful on both occasions. My daughters have written “where I’m from poems” in school (sometimes with a guided template) and I wrote a very long one at a poetry retreat. The power of the exercise lies in defining what the prompt is asking. You can be from words you’ve read, the poetry that helped make you who you are, as much as you can be from cornfields in Iowa or the streets of New York City. Try writing one. Give it a couple months and write it again. It is an exercise in redefinition, in assessing who and what has made you who you are. I love that Alexander and Patterson imagine Ali’s voice this way.

For a more complex example of a “where I’m from” poem, please read “Shahid Reads His Own Palm” by one of my favorite contemporary poets, Reginald Dwayne Betts. Betts served nine years in prison for an armed robbery he committed at age 16, and after being released, went on to graduate from college, an MFA program, and Yale Law School. His memoir, A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison, was recommended to me by some of the women I taught at Denver Women’s Correctional Facility. His most recent book of poetry, Felon, is one I have cited on Story Remedy.

Special April 2021 Feature: We’ll be sending out a newsletter guest-written by Jason Diamos, former Staff Sportswriter at The New York Times, on his experience of meeting Ali.

Please consider making a donation to American Parkinson’s Disease Association. My very close friend, Dena Paolino, is the CEO of Striking Beauties, a boxing gym for women. She offers the Rock Steady Program for people with Parkinson’s, and has these words to share:

“The Parkinsons class has taught me strength and determination. My members , who have become like family, have incredible perseverance. They work out 5x a week and refuse to let their condition dominate their lives.

I’ve also learned the importance of friendship, the power of group support. My gang encourages each other to work harder, to get through a “freeze.” Their camaraderie allows them to feel they are not battling this disease alone. To me, that is the most important benefit of the Rock Steady Boxing program.

But probably the most eye opening has been the importance of one’s spouse. The spouses of my PD (Parkinson’s disease) family are amazing. They assist with physical tasks, they coordinate their medicines, drive them to doctors, some even have to literally carry their spouse into class and hold them up during the workout. That is the true meaning of ‘through sickness and in health’. Their undying love, their patience and their adjustment to a new life that limits them to go out or travel or do things for themselves. The spouses may not have it worse than those inflicted with PD, but it’s pretty damn close.

Watching these couples, admiring their commitment to each other, puts life in a new perspective.”

“It is my hope that Black children read this book, see themselves in young Clay and know that they too are poetry made flesh.”

— - Tochi Onyebuchi, reviewing Becoming Muhammad Ali for the New York Times, 10/31/2020