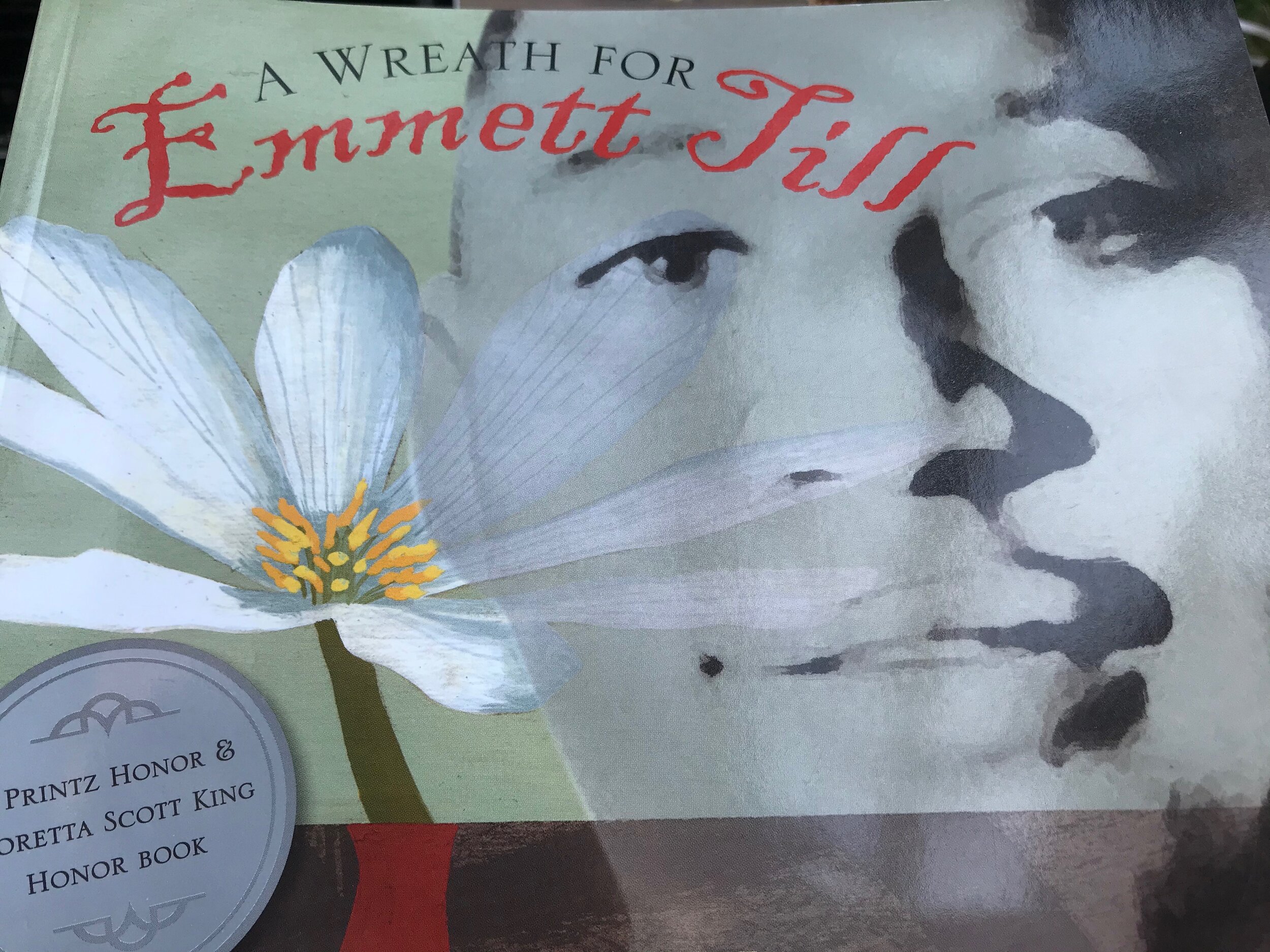

A Wreath for Emmett Till

By Marilyn Nelson

Do not let the look of this book deceive you. It is most definitely not a children’s picture book, even though it is slight, and its dimensions are small, and even though it features colorful artwork. I’m not even completely sure it is straight-forward young adult literature, but I am certain it doesn’t belong in any categories below this. It is a book I would most certainly teach in my workshops at Denver Women’s Correctional Facility with a group of very talented writers, ranging in age from their early 20’s to late 70’s. (One of whom has had her poetry published and won prizes for her writing). It is a book I would use in a poetry therapy workshop on grief and loss, or one on protest literature, or on social justice. And those would be workshops for adults too.

Marilyn Nelson explains in a very brief introduction how she came to write this poem – which is in fact called a heroic crown of sonnets -- and she elaborates in her end-notes about the allusions contained in each of the individual sonnets. Please read her notes! There is such rich historical material there, and I hope many of you will do what I call “going down the rabbit hole”: following a lead that interests you and seeing where you go with it. I’ll give you an example. Nelson, in discussing what a heroic crown of sonnets is, mentions that she had only seen one, “a fantastically beautiful poem by the Danish poet Inger Christensen.” I couldn’t just let that go. I needed to know what the poem was. Professor Google was a great teacher, and the name of the poem is “Butterfly Valley.” People have blogged about it (here’s one), and translators have written articles about it. What is most significant in terms of the context of this book is Nelson’s reason for why the rigidity of the form held such appeal for her. Nelson needed a boundary, what she calls “a kind of insulation, a way of protecting [her]self from the intense pain of the subject matter.” The barbarity of what happened to Emmett Till is almost too much to take in.

It is hard to call a poem about Emmett Till beautiful; it is much easier to use that language to refer to a poem about butterflies. Confronting the brutal murder of Till through the form of a sonnet – and not just a sonnet, but a heroic crown of sonnets! – is unexpected, to say the least. And that “unexpected” is what makes this book in fact quite beautiful. In these fifteen sonnets, Nelson goes unexpectedly deep into the story of what happened to Emmett Till in 1955 – only 65 years ago. He was a 14-year-old boy murdered for allegedly having either whistled or said something deemed offensive to a white woman. His murder belongs to a long history of racist hyper-sexualization of Black men, and the deadly results due to white men’s terror of miscegenation. It is worth noting that Timothy Tyson’s 2017 book, The Blood of Emmett Till, reveals that the white woman, Carole Bryant, whose husband was one of the acquitted murderers, retracted everything she’d said about Till. See this NYT article for more details.

Had he not been murdered, Emmett Till would today be a decade younger than my dad, who is alive and well at 89, with 13 grandchildren as his living legacy. I have made this personal so that when we confront the reality of Emmett Till’s death, we really take in how not not long ago this happened. My dad was a young man when Till died. He saw the pictures of Till’s ravaged face in the newspapers. Nelson herself addresses the loss of all the future years of Till’s life, and imagines the possibility of those years, in the sonnet that begins: “Erase the memory of Emmett’s victimhood/ Let’s write the obituary of a life/ lived well and wisely, mourned by a loving wife/ or partner, friends, and a vast multitude.” Till was and is certainly mourned by a vast multitude, but we can tragically only imagine the life he might have led. Poet Eve L. Ewing does exactly that in her very contemporary poem, “I saw Emmett Till this week at the grocery store,” that illustrates how much the tragedy of this young boy’s death still resonates today – the relevancy. It is difficult for me to look at a picture of Trayvon Martin and not think of Emmett Till.

Emmett Till’s mother, Mamie Elizabeth Till-Mobley, made the brave and terrifying decision to insist upon an open casket at his funeral. She wanted the world to bear witness to the violence that had been done to her son; to allow no one to turn away. She allowed photographs to be taken of her son’s body, and then published in newspapers and in Jet Magazine.

There is a short documentary, narrated by Bryan Stevenson, (author of Just Mercy, and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative), that addresses just what a significant role those photos played in the civil rights movement. (Please watch here with the guidance of your parents. The black and white photography is graphic and disturbing. And yet, it is despairing to have to note that young people today have seen one violent video after another depicting the deaths of young Black men and women in very recent times). Stevenson says that “these images made it impossible for white people to be indifferent”; that the pictures insured that “his face will be remembered.” He calls the death of Emmett Till, and the resulting press, an “organizing and galvanizing moment for this country.”

In this way, a direct line can be drawn from the murder of Emmett Till to Rosa Parks to the Civil Rights Era to the Black Lives Matter movement of today and “Say Their Names” (an ongoing gallery project of names, photos, and articles documenting Blacks killed in the US by police and by civilians. Emmett Till is one of the earliest people listed). Stevenson, while acknowledging the intense difficulty of looking at the images of Emmett Till’s brutalized body, also insists that “without the imagery, there would be no one who would be prepared to believe some of the violence that we’ve witnessed.” It makes me think of the lasting effect of photographic images released after the liberation of the Nazi death camps at the end of World War II. Those photos were published in Life Magazine and other newspapers, and after seeing them, it was impossible to deny the murder of millions of Jews and other Nazi victims. Along with the actual photographers, and the liberators themselves, the viewers of the photographs – even a continent away -- became witnesses to the genocide that had occurred.

With witnessing comes responsibility. All of us who have now seen the videos of police brutality, of Black men and women literally being killed on our screens, have responsibility. We cannot turn a blind eye. We cannot walk away. We need to engage, to protest, to resist. Bob Dylan, protest poet, Nobel Prize winner, witnessed through his music (including an intense ballad he wrote about Till). Marilyn Nelson turned to poetry as a way of witnessing. The first words of her book are: “I was nine years old when Emmett Till was lynched in 1955.” She grew up with the story of what had happened to him, and how that story – his lynching, and the lynching of over 4000 other Black Americans between the years 1877 and 1950 -- is a terribly tragic part of the history of the United States, but it cannot be ignored. Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative, the organization he founded, has played a huge role in documenting the history of lynching in America, including the building of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. (I encourage educators to visit Lynching in America which includes EJI’s original report, as well as lesson plans and digital resources for the high school classroom). I also encourage you to donate to EJI if you can.

I want to conclude by returning to Nelson’s book, and explain why we chose to include it. It exemplifies the power of art and activism, of reading and resistance, of poetry and protest. Nelson is asking you to recognize that within the beautiful poetic confines of a 14-line sonnet, with its strict iambic pentameter rhythm, she is addressing 14 times the brutality of taking the life of a 14-year-old Black boy for no reason whatsoever other than horrific racism, and the absolute injustice that the men who did it were acquitted. And then, after doing that, with some striking poetic imagery and language (one of my favorite lines is “some white folks have blind souls”), she offers the final poem, composed of the first line of each of the previous sonnets, which I will cite here in its entirety:

Rosemary for remembrance, Shakespeare wrote.

If I could forget, believe me, I would.

Pierced by the screams of a shortened childhood,

Emmett Till’s name still catches in my throat.

Mamie’s one child, a body thrown to bloat,

Mutilated boy martyr. If I could

Erase the memory of Emmett’s victimhood,

The memory of monsters… That bleak thought

Tears through the patchwork drapery of dreams.

Let me gather spring flowers for a wreath:

Trillium, apple blossoms, Queen Anne’s lace,

Indian pipe, bloodroot, white as moonbeams,

Like the full moon, which smiled calmly on his death,

Like his gouged eye, which watched boots kick his face.

Look what Nelson does here with a downward vertical reading of the first letter of each line! This is the wreath she symbolically lays at Emmett Till’s grave. It is an extraordinary poetic tribute. Having written this piece, I have the insight that the reason Nelson chose to proffer her work in this form, rather than say a book without pictures, and with different dimensions, is that she does not want readers to forget for even a moment that Emmett Till was a young boy, a child, in fact. Thus this “not-a-children’s-book” is formatted to look like a children’s book. I wrote at the beginning of this piece that I am not even sure it belongs in the young adults’ category. By including this book, we are asking you to embark on the very adult act of witnessing. You are brave to do so, and we hope also empowered to act, to resist, and to protest injustices wherever you see them – maybe even through art and literature, as Marilyn Nelson has so powerfully done here. RIP EMMETT TILL. Rest in power.